In 2020, Dr. Ashley Beck, an Assistant Professor of Biology at Carroll College in Helena, was awarded a workforce development seed grant from the Montana NSF EPSCoR Consortium for Research on Environmental Water Systems (CREWS). The objective of her seed grant project was to develop a Course-based Undergraduate Research Experience (CURE) for students at Carroll College. The focus of the project was to create a sequencing-based laboratory module that was integrated with the CREWS study sites to collect data on environmental microbial taxa.

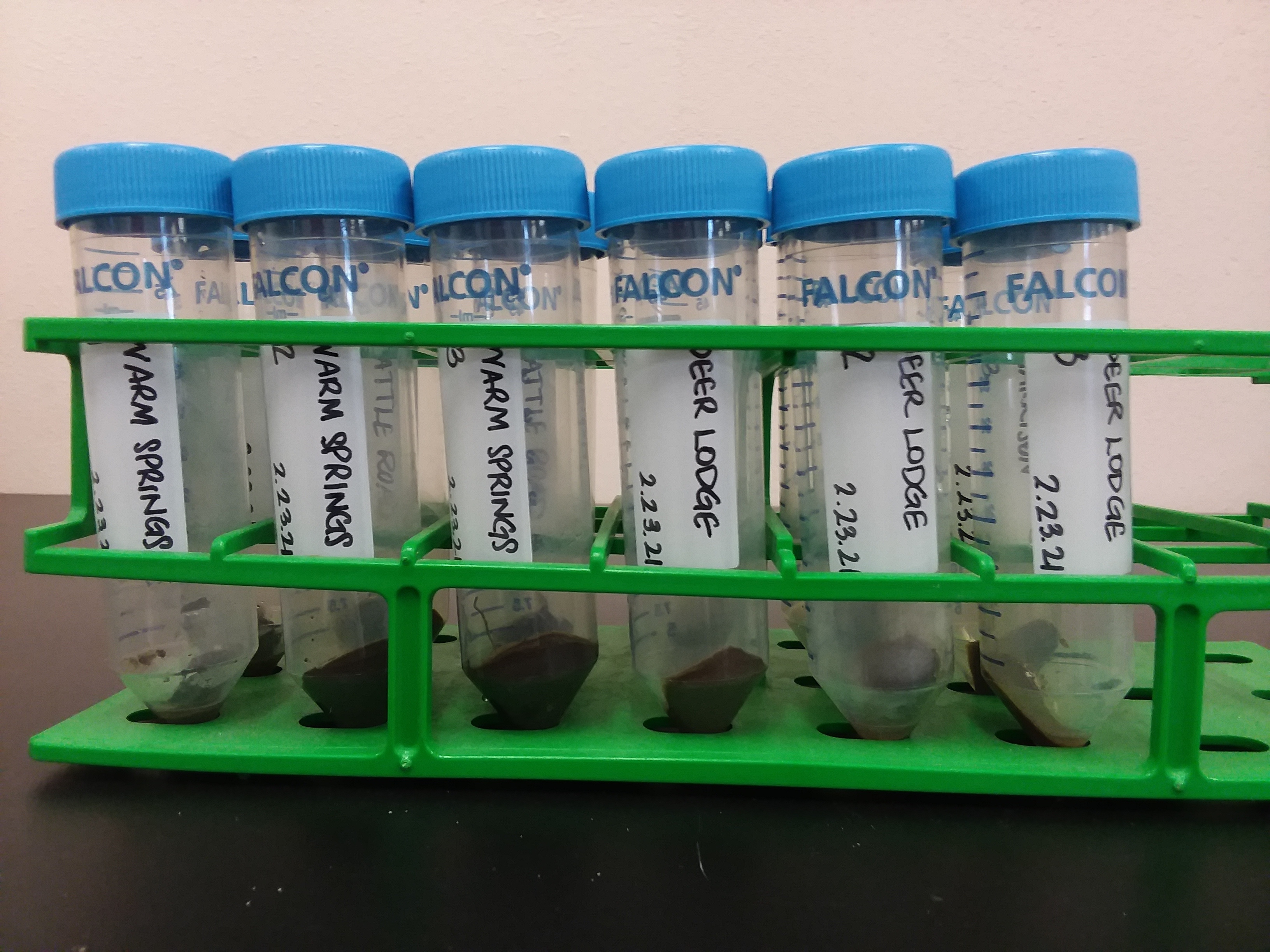

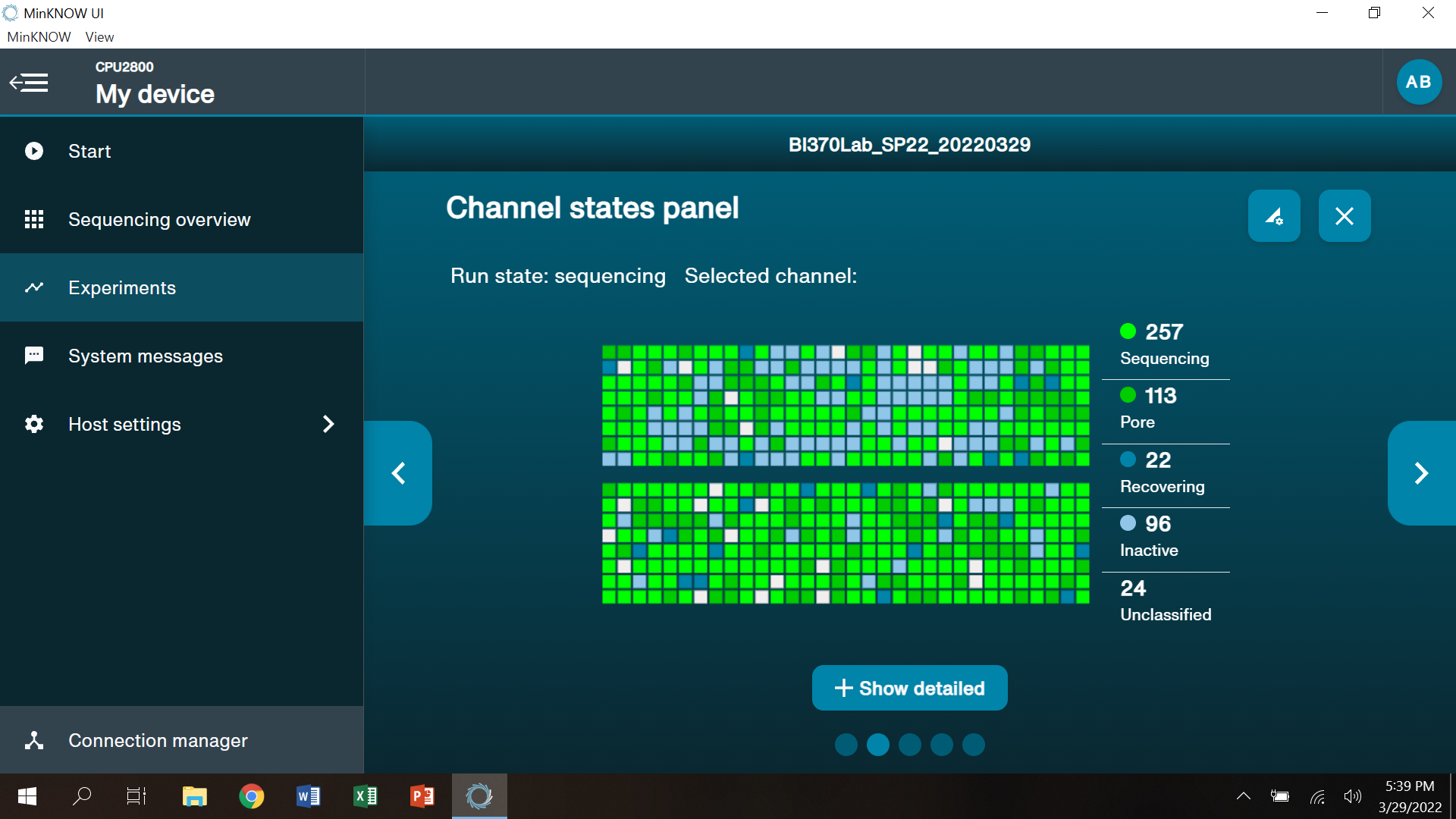

Ten students from Carroll College were chosen to be a part of the project and trained in modern molecular sequencing methods. Dr. Beck and these students partnered with the Judith River Watershed (JRW) and Upper Clark Fork River (UCFR) research teams in order to collect and study water samples, and they used a MinION sequencing starter package to sequence and analyze the data obtained from the two study sites. The students were challenged to develop their own hypotheses pertaining to microbial functions in the environment and design experiments to test these hypotheses. They used a nanopore sequencer, a relatively newer instrument, to conduct this research in order to analyze the collected data.

Beck has always been passionate about learning. As a first-generation college student, it wasn’t until she went to college that she discovered the numerous educational opportunities that exist beyond the undergraduate level. She went to graduate school at Montana State University, where she was involved in an interdisciplinary program and did rotations in chemistry, microbiology, and engineering. “I’ve always loved to merge ideas and different areas,” says Beck. “I want to encourage students to think outside of the box and mix subjects.”

Beck came to Carroll College in 2020 when they had a faculty genetics position open up. She applied to the NSF EPSCoR CREWS seed grant because she’s always thought that sequencing is an interesting research tool, especially with the new technology that has been coming out in recent years. The nanopore sequencing device is a relatively new device that hasn’t been used much in research yet. Beck knew that this device would be perfect to use because “the students could get real hands-on experience, rather than sending the sequences away,” Beck explains. “This way, students would really be involved in the entire research process.”

Exposing undergraduate students to the research process was a big reason that Beck started the CURE program and applied for the grant. When she was an undergraduate student, Beck worked on three different summer research projects. However, as an educator, Beck wants to integrate research into the classroom as much as possible, especially for students who work over the summer and are unable to participate in summer research. “By incorporating research into the curriculum, it really shows students what research can be,” Beck states. “Rather than just being told what to do, students have the ability to design their own projects.”

With the CREWS seed grant, Beck was able to help students do just that. Beck also wants the students to feel that they are not limited by going to a small school, which is why the nanopore sequencer was such a valuable addition to Carroll College. Her hope is that she can build a program based around sequencing now that they have the device. Beck says that “there are so many applications and opportunities for further research.”

One of the most difficult parts of the project was figuring out what to do with the information that was collected. “Processing the data by computer, analyzing the types of bacteria found, and trying to present it in a classroom setting was a challenge,” Beck explains. “In the scientific community in general, there are always new methods of analyses coming out that impact how to interpret, present, and visualize data. We’re still working on the data analysis, which will take some time, but it’s always a good thing to work on.”

The project proved to be a success, as students were able to work with high-level technology, develop and test their own research questions, and integrate hands-on bench work with computational analysis. Beck really wanted to make sure that the students were the ones doing the work themselves, and she made sure they were even in charge of processing the samples themselves. “I really handed control over to them, which was a little scary,” Beck says. “There’s only one nanopore, so all the samples had to be run in one batch and the students were the ones who loaded the sequencer. It actually worked well the first time, so I was surprised and impressed.”

Going forward, Beck hopes that she will be able to further develop the methodology of the nanopore sequencer and wants to utilize it in other ways. The sequencer can be used in a variety of other fields and other projects, especially those relating to environmental science like water and soil research. For instance, Beck recently took a sample from Canyon Ferry Lake to look at bacteria that could be contributing to algal blooms. There is also a pilot project being conducted this summer to study how different urbanization gradients affect deer mice, which will be done by sampling the microbiome of the mice in order to see if they are experiencing stress and how that is linked to urbanization.

By pioneering this project and acquiring the nanopore sequencing equipment, Beck is excited about what else can be done with this technology. “I hope that long-term, it will continue to be used in the classroom and help students get a taste of research,” says Beck. “The sequencer can be used in so many ways, and that’s the power of technology. Once you specialize in a certain type of technology, you can collaborate with other projects. We can now provide an additional level of analysis when it comes to genetic data and link up with other research.”

When Beck first started the project, she was nervous because it felt like a big risk, as she hadn’t personally done any sequencing. However, the project proved not only to be a fun experience for Beck and her students, but also a great confidence builder. “I realized that I didn’t have to know everything about something before I started doing it,” Beck shared. “It’s a process of getting information, learning to ask the right questions, and getting help along the way.” Beck was also proud that the students enjoyed the experience and were grateful for the opportunity. “It’s really nice to feel like I’m doing something to enhance their experience and education and help them prepare for a future in research, problem solving, or whatever else they end up doing.”